MEET THE YOGI AMONG US.

On a dimly lit handball court in the back of the gymnasium, people quietly shuffle in and take their place. Everyone moves in rhythm as the faint sound of sitars emanates from a stereo up front.

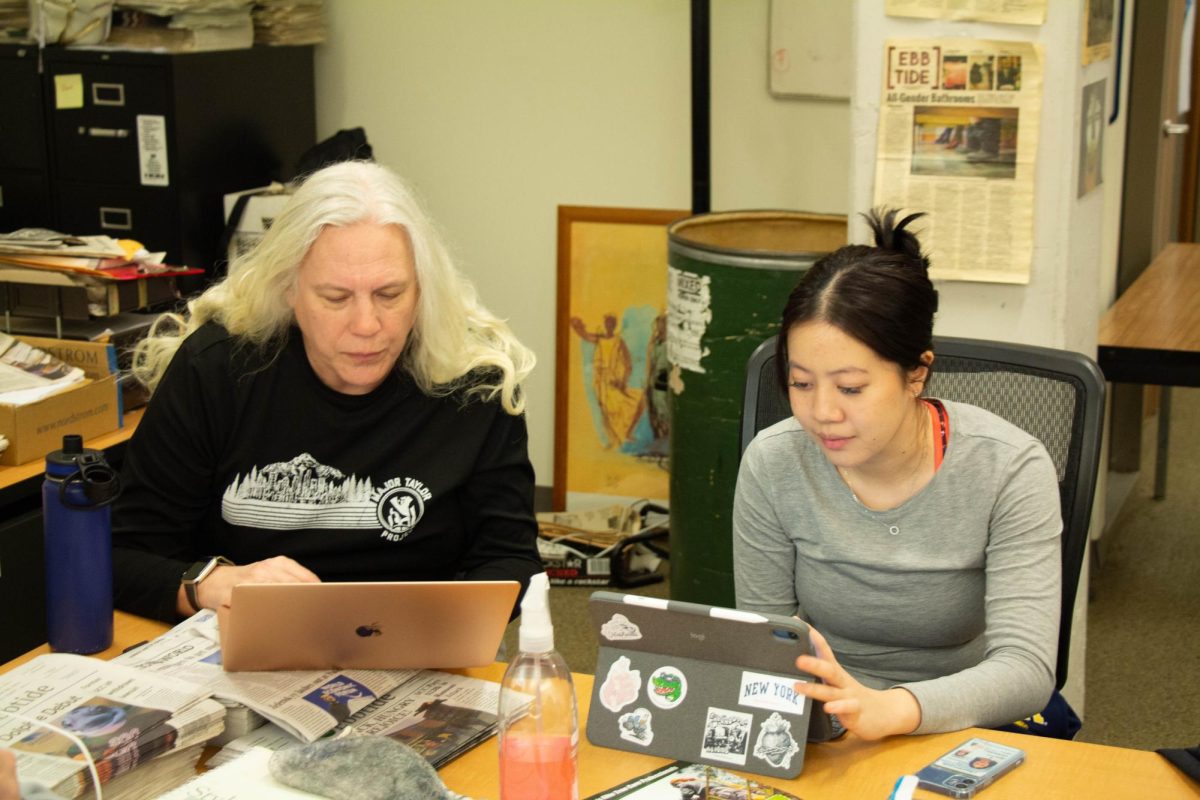

One woman stands at the head of the group, facing the rest with a slight smile. A newcomer walks into the room.

“Would you like to join in?” whispers Stacie Attridge, the yoga teacher who is about to lead her congregation in a form of physical and mental therapy thousands of years old.

Sauntering around the room holding a bottle of kombucha tea, Attridge commands respect with a warm, approachable demeanor. Her voice is pleasant and soothing, formed through years of patiently helping others work on their bodies. She is wiry, sinewy, under control.

Her following today is 10 strong, all but one of them women. Half are barefoot, half have socks. Heaters set to a balmy 72 degrees blow in air from three sides.

Once everyone has retrieved the necessary items to begin (a mat, a foam block and a strap looking like an adjustable belt), the session starts.

“Use your core rather than letting gravity take you,” Attridge says as she smoothly describes how to move from pose to pose. She guides the class through a series of positions, starting with “child’s pose,” a common resting posture, and from there she instructs her students to move to “downward facing dog.” With each transition, she reminds the class of the importance of connecting their breath with their movement.

As the class progresses, some of the names of the poses start to sound foreign and chock-full of vowels. Two poses Attridge effortlessly labels are “chaturanga” which means crocodile, and “savasana,” which means “corpse pose.” Both come from Sanskrit, an ancient Indo-European language.

Attridge grew up in Seattle as an only child. The only form of athletics her parents pursued was archery. Despite her interest in being active, her school did not allow girls to play sports until the fourth grade.

She eventually found her way into soccer, basketball and softball, which she played throughout her time at Bothell High School. Now Attridge teaches yoga both in an academic and intramural setting at SCC.

In the ‘90s, Attridge wasn’t so different from the students she now instructs: she attended SCC and went through the dietetic program to become a dietetic technician, someone who looks for the best ways to fuel the body for optimal health and wellness. However, despite her dedication to nutrition and meal planning, she does occasionally crave salty foods like chips and cashews.

Attridge regularly reminds her students to “engage the glutes,” partially because she has plenty of experience with helping people achieve their physical fitness goals. After working as a personal trainer for an all-women’s athletic club that shared space with a dentist’s office in downtown Seattle, she noticed a yoga class being offered and thought she’d give it a go.

Even as SCC’s resident yogi, Attridge says it took her almost a year to master the “pigeon pose” when she first began practicing yoga. The pose requires a lot of flexibility, and due to the many years of personal training, her body was just too tight. She consistently practiced until she was able to achieve her own version of perfection, and encourages her students to understand that yoga requires dedication to achieve excellence just like any other hobby.

She describes it like this: “If I was to walk over and pick up a guitar over there, I’m not going to start wailing like Jimi Hendrix. I’m going to have to sit there and play those chords over and over and over again until I can get that song right.”

Attridge disputes the mode of thinking that says “I can’t do yoga ‘cause I am not flexible.”

Her counter? “You do yoga to get flexible!”

Attendees of her classes find more than just their flexibility improved. “My focus here is to help reverse the negative effects of people sitting at a computer all day, the stress of having homework — that kind of stuff,” Attridge says.

SCC student and intramural yoga participant Xiang Li had a cough that she attributes to the cold weather of the Pacific Northwest.

“When I do yoga, it makes my cough go away,” she says. “After my yoga class, I can concentrate on my studies better.”

For Li, yoga is a language that can be understood universally. “Even though I can’t speak English very well,” she says, “I can understand the teacher.”

Another person who frequents Attridge’s classes is Raquel West, one of the head coaches for SCC’s volleyball team. After tearing both her achilles tendons during her volleyball playing days, she struggled to find the right exercises to help her recover.

Yoga proved especially difficult; lacking good balance, standing on one leg was a challenge for West. She recalls laughing through portions of her first yoga session last spring.

She still can’t stop laughing now, when talking about how far Attridge’s class has helped her come: “I recommend yoga to everybody,” she says. After just a matter of months, West configured her teaching schedule so she could attend yoga sessions three times a week.

Even though Attridge admits that a career in yoga is “financially not the most stable” and that “(it) doesn’t come with medical benefits,” she struggles to imagine her world without it. Even if her life took her in a totally unexpected direction, she is confident she would still teach at least one or two classes because it is her passion.

As she concludes every session, Attridge serenely says a few words of salutation while pressing her palms together and bowing her head.

“Thank you, and namaste.”

If you want to participate in yoga, check the Intramural Schedule for times and location.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

by CJ Priebe,

Sports Editor