INSTRUCTOR TEACHES FROM EXPERIENCE

It was an exhausting start of the day for everyone on campus, given that it was an early morning on the second-to-last day of instruction before finals.

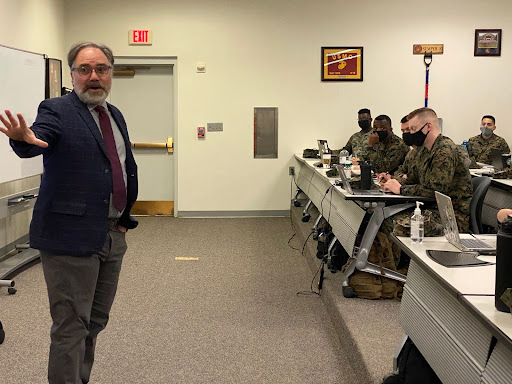

But in one of the rooms in the 1800 Building, students were not leaning on fists or falling asleep. Instead, they were silently moving their bodies and hands, their breathing barely audible, as they followed the gestures of a woman with golden hair standing in front of the whiteboard.

The woman is Jodene Anicello, SCC’s American Sign Language (ASL) teacher since last fall.

Discovering

Anicello was born deaf in 1958. However, her parents didn’t realize she was deaf until she turned three.

One day, Anicello was playing with her siblings when a new babysitter knocked on the door and her siblings ran over to see who it was. Anicello, however, remained seated on the ground and played on her own, undistracted by the sound.

“I think your daughter might be deaf,” the babysitter told Anicello’s parents.

Her parents, however, initially dismissed the babysitter’s concern. They thought she was just like her brother, who was a delayed speaker. Until one day, the babysitter heavily banged a pan on the ground to test her and she did not respond. Her parents then took her to the clinic to have a hearing test and discovered her deafness.

“Part of my ears were not functioning properly,” she said. “I can hear (only) low frequencies, low pitches and my dog’s barking.”

Anicello remembered watching her dad fixing his car one time. He would point and gesture at the tools he wanted her to get for him.

“I didn’t know if it was one tool or the other, so I’d bring them all over and he would give me a thumbs-up,” she said, and according to her, that was the way she and her father communicated.

Once Anicello was older and knew how to talk, she and her father were able to have conversations, even though she had to read his lips. Though he spent most of his time working to provide for the family, her father once told her, “I’m so sorry that I never learned sign language,” after realizing how much she loved ASL.

“(My parents) absolutely accepted that I was deaf and encouraged me to do anything I wanted,” she said. “(They were) very patient with me.”

Growing

The history of sign language started in 1771 in France and it soon emerged into different languages, such as ASL in 1817. During the 1860s, a debate about the mode of communication to be used in deaf education began. The European countries believed that deaf students should learn lip-reading and use spoken language to restore themselves into mainstream society. In 1880, a conference ensured the dominant opinion of oralism and the U.S. followed the world to ban the use of sign language communication until the late 20th century.

Because of that, Anicello said she had a limited childhood and that she had less time to play while growing up. Fitting in as a deaf person was her predominant goal as a child, so she had to do homework training and speech therapy for one hour every day, five days a week, for 16 years.

“I had no life at that time,” she said, laughing.

Studying at Green Lake Elementary School, she attended a mixed class with deaf and hearing people without any help from an interpreter.

“So if someone walked in the way of (the) board, then it was completely gone. After the person who was blocking went away, I would try to figure out what was all about from the writing on the board,” she said.

There was a beautiful girl, she recalled, with sparkly blue eyes and eyelashes to match, who was also deaf, sitting next to her in fourth grade. They would communicate with each other using signs, and the girl helped her pick up science and mathematics. They stayed best friends even after the girl got married and moved to New Mexico.

In 2004, Anicello decided to get a cochlear implant despite the debate among the deaf community — some deaf people believed they should endorse their disabilities and live with it, while some wanted to experience the hearing world and better communicate with hearing people. But Anicello said she didn’t mean to change her deafness by using the cochlear implant.

Without the cochlear implant, she said she felt stuck inside a machine pushing out a constant barrage of white sound. But the moment she tried her implant, she heard all the sound she had never heard of before. She was able to understand the source of that white noise.

“Sometimes I felt sorry for hearing people who had to deal with all of the noise,” she said. “It’s never quiet. You can never turn off your ears.”

Yet hearing the sound of a key turning in a lock for the first time was earth-shattering for Anicello. She kept taking the key out from the lock and putting it back and opening the door again. Every sound was fascinating, music to her ears.

She spent years identifying different sources of sound, and she thought about her future in the auditoral world, contemplating becoming an interpreter or teacher.

One year after her implant, she took a job as a manager for developmentally delayed adults. One day while she was walking downstairs, she was startled by the presence of another person and fell down three stairs, breaking her implant.

She wasn’t able to get a repair on her implant, due to the cost of $60,000.

“So I became deaf all over again. I couldn’t make a connection with the world,” she said.

It had been challenging enough for her in the first place. Her challenges, however, didn’t end there.

On a Friday in 2005, her first service dog Chewie, a cocker poodle, died at age 11 with cancer everywhere in his body. Despite experiencing a lot of pain, Chewie kept working until the day he died, she said.

Anicello said Chewie completed her by doing things her ears could not. Oftentimes, in her class, Chewie would curl up into her coat on the chair and wait.

One time a phone rang during class, which drew Chewie’s attention, making him search for the sound. Anicello looked around the class and pointed at a couple of students whose faces had turned red, laughing, and said, “My dog caught your phone ringing.” After that, he became the voice police in the class and spied for her.

Although she has a new service dog, Luke, she said she will never forget how Chewie completed her.

Within two months of Chewie’s death, her mother died of a massive stroke. Her father also passed away in 2011.

Losing three of her loved ones, Anicello was depressed for a while, but she said she thinks it was just a big challenge in her life.

“Anyone who lives in this world is going to have challenges,” she said. “And my disability didn’t need to be a challenge.

“That is something that (needs to be) accommodated and worked through,” she continued.

Teaching

In the classroom, Anicello was going over a nature-themed worksheet as her fingers danced to demonstrate the signs for the words “grass,” “lake” and “tree.”

She bent her index finger and put it on her nose. It was the sign for “eagle,” mimicking the beak. She stooped down and pretended to be an eagle hunting for food.

Students followed her signs and giggled every time she made a joke.

Anicello said she loves teaching and has been a teacher for 33 years. Other than teaching ASL in colleges, she was a nurse’s assistant for elderly people, a licensed cosmetologist, a program manager and job coach for people with developmental disabilities and a teacher for homeschool kids.

“I’ve always been a teacher, always, always, always,” she said.

She said she picked up signs quickly when her deaf friend showed her, causing her to go to school and became an ASL teacher in 2002.

In an SCC student’s first ASL class in the series of three, they have to turn off their voice in order to feel the deaf world. Anicello hands out a contract to students for being in the classroom. Everyone has to sign it and obey the rules, like phones have to be off and eyes have to be on each other. Oftentimes students just watch her movements and mimic her signs.

In order to force students to observe using their eyes like a deaf person, she also turns off her voice while teaching because that could shut down students’ default reception to use both their ears and eyes.

“Voice has to be in the head, not out of the voice box,” she said, “but while communicating in ASL, their ‘voice’ is in their hands.”

Rather than having a quarter-long dull lecture, she often brings mini deaf games to class and allows students to get involved.

“They can’t use their mouth. They have to sign and read signs to understand what their teammates said,” she explained.

Jason Hood, an SCC student who took her class last quarter, said he took Anicello’s ASL class because her way of teaching was less stressful than other language classes.

“She made it fun and (it’s) kind of a goofy way of teaching,” Hood said. “You never felt intimidated by her teaching styles.”

Anicello said her motto in life is “If you put in effort, nothing’s impossible.” As a teacher, she said she always confronts challenges because students are individual learners who learn differently, so she would put effort into researching a different teaching method, in order to help every student understand ASL better.

“You can learn movements, you can learn expressions, you can learn communication with anyone,” she said.

“It might make life a little easier if I was born hearing,” she said, considering she might’ve been able to communicate better with her family.

“But I like who I am, this is my life, and so this is what I’ve accepted.”

By Frances Hui,

Political Editor

Photo by Frances Hui