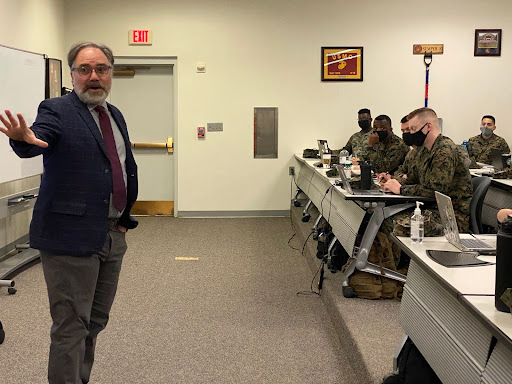

SCC’S MIMI HARVEY

If you saw Professor Mimi Harvey as a child in the prairies of Nebraska, rounding up the neighborhood kids and pretending to teach, you might have expected her to become the teacher she is today.

What you wouldn’t expect is the story that got her here.

Growing up in a family that moved at least every two years, Harvey said she “never developed a real rounded sense of place.”

“I can pretty much … move without being upset and find a new life,” she said. “I got very skilled at entering a new neighborhood and school.”

Every time Harvey’s family would move, “I would make my mom pack the baking supplies in the car, not the moving van, so she could bake cookies as soon as we got to our new neighborhood,” she said.

Pulling up to their new house, “I would be the first out of the car and would start canvassing the ‘hood,’” she said.

“I would go to each house and introduce myself, ask if they had any kids my age to be my friends and if they had any kids my siblings’ ages,” Harvey said. “Finally I would invite the kids and their siblings to my new house for homemade cookies. It worked every time! Instant friends!”

Unlike Harvey, many of us would see being the “new kid in town” as difficult enough without introducing ourselves to the whole neighborhood our first day there. However, that was not the only thing Harvey saw differently.

“I was born with serious vision issues,” Harvey said. “I had double vision and no depth perception, I had some surgeries, wore glasses when I was one-and-a-half and had been told all my life that ‘nothing can be done other than corrective glasses.’”

Throughout her life, Harvey saw everything as if it were a mural with no depth and only dull edges.

However, Harvey didn’t let that hinder her ability to connect with others.

These days, Harvey teaches three communication studies classes: Introduction to Communication, Communication for Social Change and Critical Intercultural Communication. The last two analyze power and privilege and also fulfill the multicultural requirement.

Harvey takes a mindfulness approach to her classes, meaning she teaches students to “become more aware of their own built-in biases, reactions and stereotypes,” Harvey said.

Much of what Harvey teaches stems from a decision to move out of the U.S.

Building A University

At 26, Harvey moved to Canada with her husband, Brian Harvey, who was an educational psychologist. During that time, Harvey gained a background in intercultural communication from her studies at the University of Victoria, B.C. where she earned a bachelor’s degree in Chinese Language and Pacific and Asian Studies.

Due to their credentials and passion for travel, the two were asked to work on a project in Indonesia that would be funded by the Canadian government. And so Harvey and her husband went to work with a team in Indonesia building a distance education university. The project would end up lasting over 10 years.

The distance education program was similar to online schooling today, just without all the new technology. Material was sent to students by mail rather than through the internet, then the students would work on it and send it back.

It was especially important in Indonesia, since the country “covers 2 million square miles of ocean and close to 13,000 islands,” Harvey said. The Indonesian people had “mind-boggling obstacles that we would never even think of” just to get an education, she said.

Mastering Communication

It was Harvey’s work with the distance education university that led her to develop a curiosity about Indonesian culture and language.

She recognized that women faced a much greater challenge in accessing education due to cultural and familial reasons and wanted to better understand those reasons in order to share them with the university administration and government.

Thus Harvey decided to get a master’s degree in communication and social foundations, also from the University of Victoria, B.C.

Her research for the degree was on Indonesian women studying through the distance education university she helped build, and she spent a year interviewing the female students.

After her research was done, Harvey found herself on a plane, flying to South Korea for a job working in a culture and language institute.

“I didn’t know much about Korea other than what I had learned from M.A.S.H.,” Harvey said. “I thought it was a great opportunity.”

But when the flight attendant brought her a plate of mysterious Korean food she couldn’t quite identify, Harvey thought to herself, “I’m going to starve to death,” she said, laughing. However, she later learned to love Korean cuisine.

The cultural learning curve for Harvey in Korea was huge and steep.

“Wouldn’t that be funny if my son and your daughter fell in love, our family’s would be joined?” Harvey recalled saying to her friend Sophie, to which Sophie replied, “I’d kill myself.”

In response, all Harvey could do was laugh until she realized Sophie was being serious. Confused and shocked, Harvey left.

Later researching Korean culture and history, Harvey better understood Sophie’s reaction. With ancestor worship and Korean culture having been attacked so many times, “the idea that her daughter would marry out of Korean culture was a little death for her,” Harvey said.

“We had a really good talk about it and I think we both understood each other and our cultures so much better,” Harvey said. One of Sophie’s daughters went on to marry a man from India and Sophie loved him, Harvey said.

Pushing Onward

After spending three years in Korea, “I still had that question in my mind, how do people cross borders? What is the best way to help people see across these huge divides?” Harvey said.

Harvey applied and got accepted to the University of Iowa with a full ride scholarship for her doctorate in communication studies.

Being fluent in Indonesian and relatively familiar with Korean culture and language, Harvey said she was in a unique position — her doctoral research focused on the over 40,000 Indonesian migrant workers living in South Korea.

During that time, Harvey said she became “very close with a number of migrant workers,” including a woman named Nurfatatik, who still calls Harvey “mom.”

Nurfatatik’s life as a migrant worker in South Korea who was shipped to Saudi Arabia wasn’t unusual, “but she was unusual in that she was extremely bright,” Harvey said.

If Nurfatatik had access to a good school and colleges, “I have no doubt she would have been amazingly successful, but she didn’t have the opportunity,” Harvey said.

It was Harvey’s method of examining the power dynamics within these intercultural relationships and the critical approach she used to study power and privilege that led her to want to teach communication courses that deal with inequalities and “-isms.”

Eventually Harvey made her way to SCC where she’s been doing exactly that for the past 10 years.

Seeing Clearly

Around four years ago, the opportunity for something more to be done about Harvey’s double vision and lack of depth perception came in an unexpected and rather startling way that left her struggling to keep her balance.

It started with a bout of shingles that took Harvey’s ability to hear in one ear.

“Because you use triangulation with both ears in hearing, it really wreaked havoc on my balance,” Harvey said.

“All my colleagues here at (SCC) were so amazing, it was the middle of the quarter and over a weekend I was completely incapacitated,” she continued. “They stepped in, taught my courses and finished off the quarter for me and then donated sick leave so that I had winter quarter to recover.

“I knew the reason I came to teach here at Shoreline was because of the commitment of the people, but it really brought it home to me how much of a community it really is and how supportive everybody really is,” she continued.

While visiting a physiotherapist who was helping her regain her balance, Harvey was directed to an eye doctor who the therapist thought could help correct her vision.

Though originally skeptical of the idea, Harvey decided to take the referral.

Following her visit with the eye doctor, Harvey “embarked on a couple-year journey to develop stereo vision and depth perception, not really knowing if it was possible but believing that it was,” she said.

About a year and a half into weekly therapy and daily eye exercises, Harvey started to experience the three dimensional world for the first time in her life.

The next week, Harvey was doing an eye exercise with her therapist when the object she was looking at became clear but unfamiliar.

“All of the sudden it looked like it was hanging in space three dimensionally and I stopped dead,” Harvey said.

Harvey’s therapist asked, “What are you seeing?”

Harvey replied, “I don’t know, I don’t have any idea what I’m seeing… It looks like this object’s hanging in mid air.”

Then her therapist told her, “That’s how everyone sees all the time.”

“I was like, no way!” Harvey said.

That visual clarity would come and go and the next time Harvey’s vision fully came back to her was while she was teaching.

“I was in class and there was a rather handsome young man in the front row. I mean, all the girls in the class were gaga and, as I do, I was looking at different students as I was talking,” Harvey said.

“When I looked at him, all of the sudden he was in 3-D and I literally stopped talking. I was just staring at him, and it was so embracing, everyone was looking at me like why are you staring at him?” she continued, laughing.

“Then it started happening more and more and now it’s pretty much all the time,” Harvey said. “I can’t even describe how it’s changed, how I see the world. It’s more interesting, I mean there are corners and the edges of things are sharp.”

Though the experience of finally being able to see in three dimensions started with the difficult loss of her hearing and balance from shingles, Harvey sees the silver lining in what could have been a strictly negative experience.

“I think it’s made me more compassionate around the struggles that people face, even ones who look like their lives are perfect. A lot of us carry around struggles that don’t show,” Harvey said.

By Nathan Wilford,

Staff Writer

Photo by Nathan Wilford