The desire to create graffiti has nearly as many manifestations as the street art community has mediums. Whatever label is given to the medium, if it’s yarn bombing, spray painting or releasing balloons above a lake, public art, and street art, are in Seattle — and the world — to stay.

Graffiti can be an interactive part of a community, and whether the graffiti is hygienic or not is not always a concern. Seattle’s own Gum Wall near Pike Place Market is an example of this.

The Gum Wall is not in fact a gum wall. It is a gum alley. There is gum on the walls, on the ground, in the windows, on posters and in giant globules hurled (or placed?) further than any human without the aid of tall friends and perching on each other’s shoulders can reach.

There is gum squished to form heart shapes and lovers’ names. Even phone numbers. There is gum forming Hitler-mustaches on some posters that were already anti-Trump. The gum wall has been removed and put up again because people love interacting with their community in an artistic way, even if it is slightly gross.

Yarn bombing, a non- traditional form of graffiti, involves covering public items with what can be called form- fitting knitted sweaters for objects. These sleeves can cover street lights, railings, fire hydrants, bridges, roommates of yarn bombers who are heavy sleepers, trees and public statues. Yarn bombing is done by knitting a sheet of yarn, fixing it around the object they wish to vandalize, and sewing the two ends together.

Magda Sayeg is thought to be the founder of yarn bombing — also known as guerilla knitting — beginning in 2005 with the creation of a knitted and crocheted- over bus in Mexico City. She continues her work as a textile artist today.

Her more recent works include sweatering all of the heating ducts at the offices of Etsy.com in Brooklyn and knitting covers for 69 parking meters for the Montague Street Business Improvement District in Brooklyn. Currently, Sayeg has five assistants to assist her knitting, and they work on looms instead of with needles to produce a higher volume of art.

According to the Seattle Times, yarn bombing takes a matronly craft, knitting, and a maternal gesture, wrapping a warm blanket around something cold, and puts the idea out into the cold, concrete streets of cities. The art form has been affectionately nicknamed “Grandma Graffiti.”

Two yarn bombers from Vancouver created a guide for knitters to become accustomed to the law- breaking involved in their craft. Leanne Prain and Mandy Moore wrote “Yarn Bombing: The Art of Crochet and Knit Graffiti” in 2009. It is largely an instructional book, containing tutorials with tips like, “Wear ninja black to avoid capture.”

The book jokingly self-stereotypes yarn bombing artists, instructing readers to get off their rocking chairs if they’re tired of making Christmas sweaters. And, most importantly, to “take back the knit.”

A Seattle quilter Laurel Strand photographed and wrote about the horse statues in Ronald Bog Park in Shoreline being yarn bombed in September of 2013.

This local installation was not the standard tube-of- yarn-around-a-tree style yarn bombing. The park’s horses were fitted with small, green sweaters. Nearby trees were wrapped in fleece blankets, and lollipop-like discs of knitted yarn were hung from branches. Hanging alongside the discs were a tiny sock and a little green turtle.

An artist had tied three groups of green balloons to weights, and placed them in the park’s lake. They floated above the still water like grapes on a plate, “Floating this way and that in the breeze,” according to Strand.

The installations, Strand later learned, were an organized, legal project, part of the Summer Set Festival organized by the City of Shoreline, and was directed by local artist Cynthia Knox with the support of the Shoreline Parks Board. Artist Lorenzo Moog was responsible for the piece that confused Strand most when she happened upon it: sections of a dead, fallen tree seemed to have turned bright orange.

Moog had wrapped the tree in shiny orange material, meticulously and exactly, so it appeared as if the tree had become something bright, rather than being covered in manufactured wrapping material.

In Moog’s words, “The fallen tree is alive again, only this time with both color and line.”

Public art like this, created by artists and left to be found by anyone, is often playful, just as graffiti can be. Though some artists argue about definitions, this installation was not graffiti, as it was legal. Just like most graffiti, though, and unlike most art in a museum, it is left to be found without an immediate explanation of exactly what it means, or how the artist wants to make the observer feel.

In Shoreline, Seattle and around the world, in the face of ever-stricter laws and public opposition, vandals and street artists find ways to make art playful and fun — especially when they get to do something they’ve been repeatedly told not to.

In Glasgow, a statue of the Duke of Wellington stands outside the Gallery of Modern Art. The large statue of the Duke sitting atop his horse was created by Carlo Marochetti in 1844. The people of Glasgow have taken it upon themselves— since the 1980s, some believe—to place a singular traffic cone upon the head of the Duke of Wellington.

The Glasgow City Council strongly discourages this astonishingly persistent form of vandalism. Because vandals are so determined to constantly replace the traffic cone on the Duke’s head, the perpetual cycle of removing the traffic cone has been estimated to cost the city 10,000 pounds a year.

In an effort to avoid this costly clean up, the Glasgow City Council proposed raising the statue further off the ground and making the statue’s base twice as high as it was originally, thus making it harder for vandals to reach. This 65,000 pound proposal was met with such immediate and angry public outcry that it was discarded.

According to the BBC, Glaswegian photographer Steven Allan and Scottish musician Raymond Hackland created a Facebook campaign titled, “Keep the Cone.” He started a petition that stated, “The cone on Wellington’s head is an iconic part of Glasgow’s heritage, and means far more to the people of Glasgow and to visitors than Wellington himself ever has. Raising the statue will, in any case, only result in people injuring themselves attempting to put the cone on anyway: does anyone really think that a raised plinth (statue base) will deter drunk Glaswegians?”

The petition received more than 72,000 likes within a day of its creation, and 10,000 signatures. The National Collective, a Scottish independence organization that describes itself as an open and nonpartisan group of artists and creatives, even organized a rally in support of the public’s right to place a cone on the public statue.

The street art community isn’t all tree sweaters and local traffic cone traditions. Many artists dislike the way the art world works.

In an art gallery in Manhattan in 2015, the famed graffiti artist Banksy had a painting that was, like much of his work, critical of the art world. It was a modified version of his iconic stencil, a man rioting, with a bandana hiding his face, poised to throw what looks like it should be a molotov cocktail, but is instead a bouquet of flowers. In the modified piece, the rioter holds a book. If the painting’s viewers look closely, they will see that the book’s title is “Art for Dummies.”

In one of his public, illegal pieces, Banksy stenciled the silhouette of a person throwing up, but their vomit was a flowery shrub at the base of the wall, marrying the physical world with a piece of art.

Much of his work centers around violence, war and the innocence of youth. One famous piece is of a soldier in uniform, heavily armed and a little girl half the soldier’s height in a dress, patting the soldier down.

The blurring of lines between art and vandalism, between graffiti and interactive art is part of what makes it such a popular and diverse type of art. Anyone can take part in it, and the artists create their own rules to abide by. Not all artists will follow these rules. There is mindless vandalism of various parts of the human anatomy, there are grammatically incorrect, hateful slurs written in bathrooms and on playground equipment. It is up to each community — each town, school and neighborhood to foster the kind of environment that encourages the art the community wants to see. A good place to start this is to increase the number of legal walls for artists to paint.

Banksy said it best in “Wall and Piece,” his book published in 2005, “Imagine a city where graffiti wasn’t illegal, a city where everybody could draw whatever they liked. Where every street was awash with a million colors and little phrases. Where standing at a bus stop was never boring. A city that felt like a party where everyone was invited, not just the estate agents and barons of big business. Imagine a city like that and stop leaning

against the wall — it’s wet.”

– Nellie Ferguson

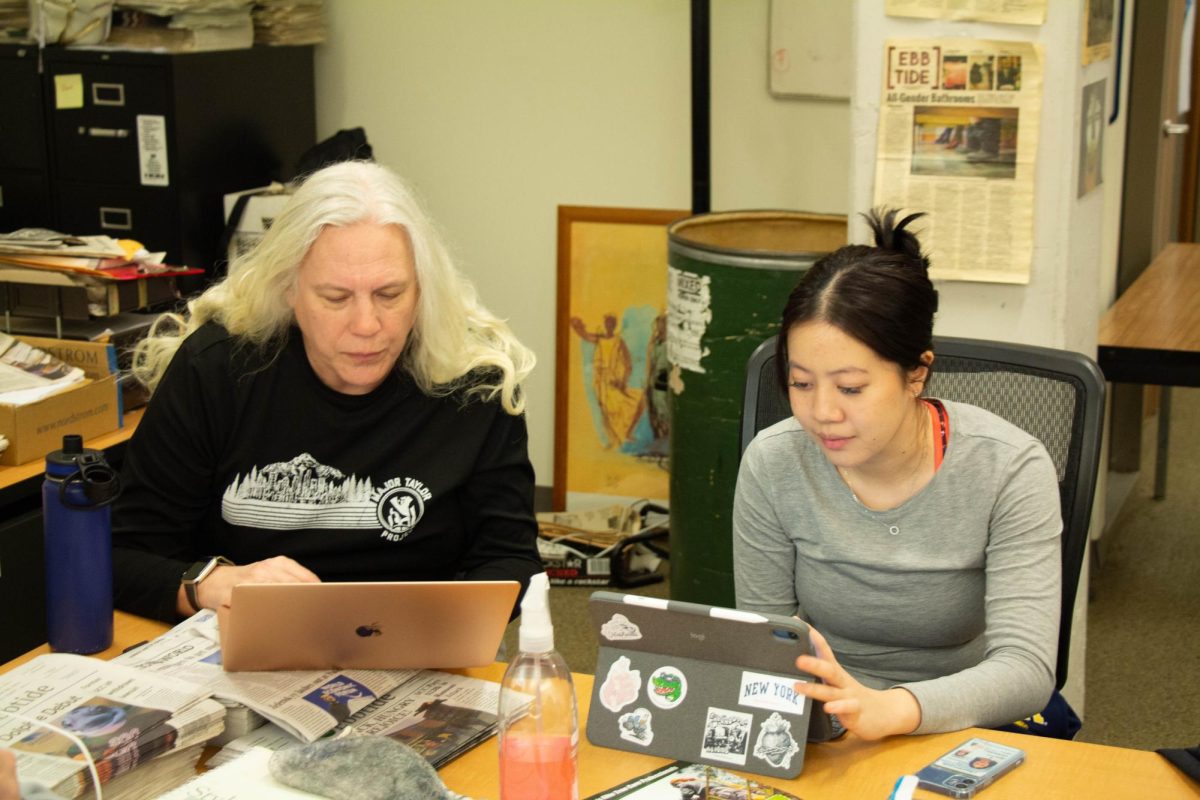

– Photo by Nellie Ferguson