MUSIC TEACHER’S UNEXPECTED JOURNEYS

Creating sounds used by stars like Tina Turner, Dire Straits, Rick Astley and Michael Jackson was not a course Dave Bristow had set out for when he was young.

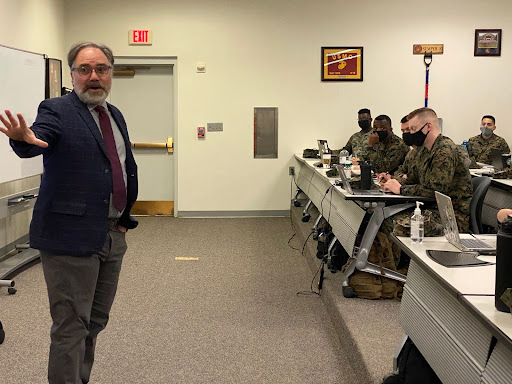

Now nearing his 70s, at 6-foot-3, SCC’s towering British digital music tech faculty finds himself sharing his past with SCC students and teaching them marketable skills in the music industry.

Growing up in East London in the ‘50s, Bristow took piano lessons until he was eight or nine.

“I discovered when I was little, I could entertain people,” Bristow said.

He gave up piano for a short time and picked up the guitar, but as he got older he started tinkering with pianos he found in the common rooms at school.

“When you can pick out a tune on the piano and you’re a boy, 14, 15, it’s good if you want to pick up girls.”

The schools broke the children up rather early into science or arts as their focus. Bristow liked art but was told, “You can’t be in the art class. You have been put down for metal working instead.”

Eventually he found he was fascinated by science and pretty good at it as well. Having a direction for his future, he went off to university in Birmingham. But after one quarter, he found he was not meeting the steep academic curriculum of the engineering program and, with permission, returned to school the following year on a path toward a degree in psychology.

However, while he was in college, he had one overarching question.

Why is it that when you play a certain chord — like a major seventh, which has tones that complement each other — it evokes the emotions that it does? Bristow was hoping a music psychology class, also known as psychoacoustics, would answer that question.

The class ended up being a study on how the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” was a concept album. It was not what he was hoping for, but the interest had been sparked in his mind.

While at university, Bristow formed a jazz-rock quartet with some other local musicians. The group was called Poliphony and they had a jazzy British 1970s sound. Bristow played flute and a Wurlitzer keyboard with his band members on bass, drums and a wah-wah pedal guitar.

At his computer in his SCC music building office, Bristow found the album from 1973 on YouTube. As the first song started playing, he sat back in his chair and let out a joyous laugh as his cheeks lifted and the laugh lines and outside corners of his eyes became more defined.

The album opens with a fat “wah wah” sound from the guitar, before the drums, bass and flute break into funky grooves. Energetic and wordless, the music allows for listening without the need to understand a message. You can just go back to a different time.

After Bristow finished his degree and started doing research in psychology, he changed paths again. He left that job to take on one at a local music shop managing the keyboard section.

Bristow convinced the owner of the shop to install glass walls around the little “L” shaped area of the shop floor where the keyboards were kept so customers could try them out in an isolation room. But the truth was he wanted to “keep the plebs out,” Bristow said, and the glass gave him a certain freedom.

In fact, his curiosity for sound and science had him messing around with all the keyboards; he was seeing how they worked and what sounds he could create.

In the shop one Saturday morning, Bristow was informed that there was to be a demo at a local hotel that evening and Mick Abrahams, from the band Jethro Tull, would be doing the guitar demo. But the man who was supposed to demo the Yamaha keyboard that evening with him was sick.

The shop manager asked if anyone could demonstrate the Yamaha CS 80, so Bristow filled in.

“It was a boatload of fun,” Bristow said. This one gig turned into a weekly demo gig around England, then rolled into trade show after trade show in the late 1970s, following whatever path Yamaha threw at him.

In 1980, Bristow was about to go on a trip to Sweden when he got a call. Yamaha had canceled the trip. He felt disappointed until they told him why: They were flying him to Japan to check out a new keyboard, the GS-1, a precursor to the DX7. Yamaha wanted him working on programming the sounds for the new Yamaha DX7.

At the end of three years, when Bristow went back to Japan, he arrived with 16 or so programmed electronic sounds and, with help from another programmer, they had 32 sounds, which they thought was adequate. It was not. They were given a firm deadline of one week to bring that number up to 128.

They achieved their goal; the DX7 came out in 1983, and became the world’s top produced electric piano. Bristow began traveling the world with it. He would do a couple in-store demos on the weekend and he would play local clubs during the week.

“It was a little bubble world,” Bristow said, referencing the way he was engulfed in the demo/touring life.

Eventually he landed in the U.S. in 1984 when he found an opportunity to work for E-MU Systems in Santa Cruz, Calif.

Then, in 1985, Bristow found himself in Paris at the Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music (IRCAM) where he ran a MIDI studio, which allowed communications between a digital interface and a variety of electronic musical instruments or computers.

He was finally in a world of psychoacoustics. He had found a place to explore the questions he wanted answered back in college, the questions of why sounds sound the way they do. He would be able to work on FM synthesis, programming, electronic music, sound and more academic music.

In the same room as him at IRCAM was Miller Puckette, who developed MAX, a graphic DSP interface for lighting and sound controls at concerts and stage shows.

In the early 1990s, Bristow started playing around with sampling and filters as he continued to work with Yamaha, developing technology for phones and games.

Bristow moved to the Seattle area, as it looked like a cool place to work from a home studio. He taught at Olympic College and ran a non-profit community music school.

Sending out resumes in 2011 landed him in his role at SCC.

“(I) liked the idea of becoming more involved in music/tech education in general, so I was pleased to make contact with SCC,” Bristow said.

Now teaching digital music and MIDI at SCC, Bristow has been working with his Advanced Electronic Music Production II class to add music and sound effects to a 2D video game (think classic Nintendo), with a focus on client-based projects.

“You don’t realize there are so many consumer-based advertisements, games, documentaries and podcasts; all of them have music,” student Hannah Carson said. She showed how the music changes as a little bearded man, dressed in a green hoodie, comes in contact with zombies and food in an 8-bit game. The sounds for moving, eating and taking damage all had to be created using a slew of programs.

But working with clients can be difficult.

“We only have about 250 words to describe sound,” Bristow said. “Whereas there are over 2,500 words in common use for all visual queues,”

“What is sound, how do you describe it? If you need to communicate a thought, it is perfectly okay to use the words, ‘Sounds like,’” Bristow said, clarifying that the examples we give need to be something people can relate to. “It’s no good if I said it sounds like a Black Orpington hen if you don’t keep Black Orpington hens. But if you do, as I do, you can compare how Black Orpington hens sound. (Although) we could say it sounds like a clarinet.”

If you go by his office while he is there, you might hear him playing his electric piano. You can hear the influence from Herbie Hancock’s early album “Crossings” if you ever hear him play. “That is a piece of music that, without question, influenced me, totally. Stuck in my mind,” Bristow said. You can hear a taste of his sound in Bristow’s current jazz trio, RedShift, which you can find online.

Bristow’s fellow faculty at SCC rave about his piano playing and knowledge.

“He is very tech savvy and we are fortunate to have him,” said SCC Music Department Chair Jim Elenteny.

As music technology changes, according to Bristow, “We have to decide: What is the balance between teaching software and teaching underlying, theoretical structures?”

Bristow said we may let go of some of the knowledge of how things function and rely on programs that do these steps for us.

You can hear examples of the Yamaha DX7 online here.

PHOTOS BY Nick Molsee