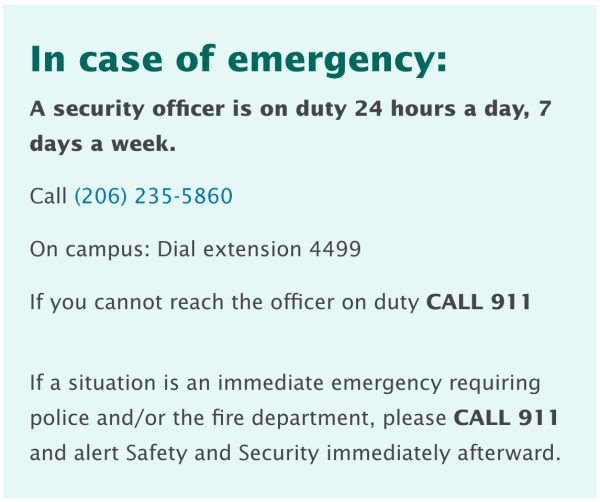

Pick any time—day or night, rain or shine—and walk through campus. Your safety will be assured by what appear to be police officers, dressed in their midnight blue and high-visibility green uniforms with Shoreline dark green “Campus Security” patches. Despite being weighed down by Kevlar vests and utility belts even on the warmest days, whether on foot patrol or parked in a squad car, they remain ever vigilant.

Their office is tucked away in a corner on the ground floor of FOSS, located in the outdoors in the elevator courtyard, behind door 5102 next to the Testing Center. Their leader is Sergeant Greg Cranson, the acting director of Safety and Security, who manages and directs the team of 12 professionals (10 paramilitary and two civilians) tasked with protecting the campus facilities and community. Cranson got his start at Shoreline in 2015 as a security officer. He, was quickly promoted to sergeant in 2017, and in 2020 accepted the directorial position.acting director role.

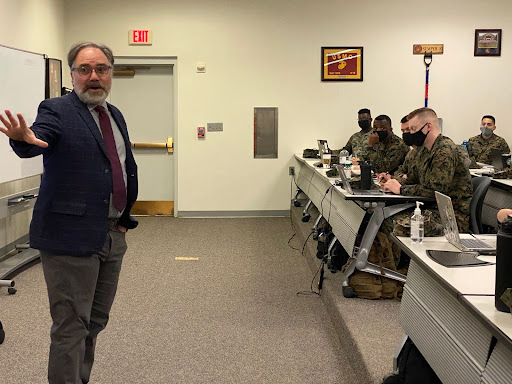

“The Marine Corps taught me a lot about leadership,” he said. Cranson served as a Marine in an infantry battalion out of North Carolina, and was discharged before deployment due to injuries he sustained in boot camp. There, he gleaned his leadership skills, communication practices, and high standards of professionalism from his platoon sergeant who, “would get on our case when we messed up, but then that would be that: unless we messed up again.”

The Marine Corps helped prepare him for working here, especially working with and for a diverse community consisting of “people of all faiths and all nationalit[ies].” There, he also honed his propensity for creativity and resilience, which he’s exhibited here on campus.

“Improvise, adapt and overcome was the Marine Corps motto,” he said were his takeaways from his tour of military service.

“In Valor, there is Hope”

Sgt. Cranson, tasked with keeping students and faculty safe from harm, shares a quote at the bottom of every email he sends: “In Valor, there is Hope.” The quote originates from the Roman historian, Tacitus, and is carved into the granite that holds up the lion statues at the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington, D.C.

A burly man who might easily be mistaken as a student here on a sports scholarship, Cranson’s arms are decorated with tattoos acquired during his time in service. A tattoo that reads, “I hunt the evil you pretend doesn’t exist,” is one he calls “cheesy”; however,but he’s integrated it into his new life as a security professional in a region where policing is looked on by some as suspect and even maliciousharmful to marginalized communities.

“And, you know, I think that’s fair,” he said. “But also, that’s not how all of these interactions are.” “I worked security for the Pride parade one year,” Cranson said, shareding in an anecdote. “It was 90 degrees, and my tattoos were out, and everybody was asking about them. I told [them], ‘you’re here watching the floats, dancing, having a good time. Police and security are here because we’re looking for that backpack that doesn’t seem to belong. We’re looking for that large truck that’s somewhere it shouldn’t be that appears to be waiting. We’re looking for that person in that heavy jacket that’s sweating and not paying attention or looks upset.’”

Policing is one of those occupations where inconspicuous vigilance is expected, right up until something goes wrong. “Not everyone can go around always thinking about it because everyone would be living in fear and no one would have fun,” he statedfinished.

Cranson and his team are on campus, thinking about and assessing campus safety and security 24 hours a day and, seven days a week.

Opportunity Locks

Take push-to-open bars, for instance — those ubiquitous, horizontal metal buttons we push to activate the locking mechanism on doors to classrooms and offices around campus. Also known as “crash bars”, they can be locked and unlocked using a thin metal hex key or Allen wrench, that is then twisted in a keyhole to lock and unlock the door.

Easily accessible classrooms are meant to be accessible by everyone until the fateful day when a class needs to barricade a door to keep a determined attacker out. Then, formerly convenient features meant to enable access become impediments to safety and security. To mitigate that, Cranson conceived of a solution.

“One of the biggest issues is we have so many different door handle devices on campus. So the thing that I put together works for any door that has the push bar and the mechanism.” Cranson devised a system to provide students and faculty the means to barricade themselves in a classroom simply by securing the door using an attached hex key.

As the video they produced in conjunction with Communications and Marketing says, “If you see this label on the crash bar, know that it has been equipped with everything you need to lock the door, should you ever need to.” The instructions on the label applied to the push bar provide a simplified version of the extended instruction provided in the video: the label is meant to guide the user through the process in times of stress.

Commercial solutions, he said, “start at $800 a door for if they wanted a more robust lockdown for the push bars,” said Cranson. One of the biggest issues is we have so many different door handle devices on campus.” Requests for more funding have to go through administration, and there is a proposal to add a safety and security fee to future tuition bills. “Getting funding for that is hard because all community colleges tend to be underfunded.”

Cranson said the training the department has received, while not as extensive as law enforcement or military training, is fine-tuned for today’s hectic campus environment. “Our staff goes through medical training with the fire department every year,” he said. They train in a variety of ways and methods in techniques such as proper handcuffing procedures, the proper use of oleoresin capsicum spray or “pepper spray” and the administration of Narcan (naloxone) nasal spray.

“Which isn’t just spraying them in the nose,” said Cranson of the opioid-blocking medicine that has saved so many people from fentanyl overdoses. The short-acting dose of naloxone can leave them alert long enough to turn down medical assistance. “They can walk two blocks down the road, the Naloxone can wear off and then they can overdose again and die.”

Emergency preparedness information specific to our campus is available online, so, “anybody can step up…there’s always people who are being valorous… everyday people that decided they wanted to save people or help,” said Cranson.

It Takes a Village…

“We do a lot of stuff where we’re trying to really be a resource and a tool for the college and not just the guys that hand out parking tickets,” said Sgt. Cranson. When it comes to scofflaws who seek to take advantage of a family-member’s accessible parking permit, “we get a lot of [Americans with Disabilities Act] violations. If we see you parking the ADA and then sprint up a set of stairs to the class, we’re going to come and we’re going to talk to you.”

“We don’t use tickets to punish. We use them to educate,” he said.

Safety and security officers aren’t just expected to be the first responders in health and safety emergencies, but they are also quite often the first responders in personal crises of a more internal nature. They are equipped not just with handcuffs, pepper spray and squad cars, but also resources for struggling students. They work hand-in-hand with the Care Team and can refer students to the Counseling Center or other resources that help them better handle a crisis.

Ideally, safety and security are about creating an environment where people don’t feel the need to resort to violence to get their basic needs met, nor as a means to amplify their unheard or unnoticed feelings of despair. “The vast majority of feedback that I give, or that I get, is positive,” said Cranson said. Cranson and his team walk the thin, Shoreline-dark-green line between protection and enforcement.

“I’ve always felt super supported by this administration,” he said. “As long as we act in good faith and we do what we’re supposed to do and we try to help people, then they’re going to have our backs.” A moment later, Sgt. Cranson spotted a lost student and offered to escort him to the Financial Aid desk upstairs.

[Edited after publication to more properly reflect Sgt. Cranson’s military service.]