A DISCUSSION ON ART AND THE ENVIRONMENT

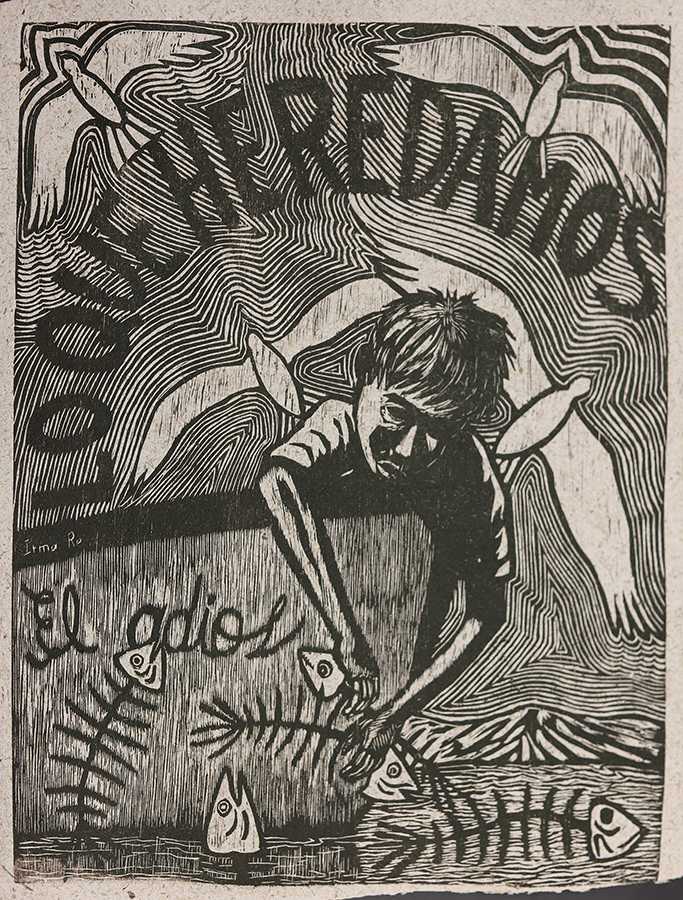

A selection of posters from the studio of Mexican artists Esteban Silva and Tania Dominguez is currently on display in the SCC art gallery.

The married couple’s work focuses on raising awareness about the environmental hazard that is affecting Lake Pátzcuaro, Mexico.

Silva agreed to be interviewed via email regarding he and his wife’s work because they were unable to come to the U.S.

Q: How long have you and your wife had your studio?

A: 18 years ago, we left the capital (Morelia, Michoacan) in search of a quiet place to live and work in art.

My trade is in painting, graphics and paper. My wife, (Tania) is a lawyer and we have three children.

The Lake of Pátzcuaro is a magical place; (it’s the) territory of the Purépecha Indians, of humble peasants, fishermen and artisans. Here we discovered a small village on the shore of the lake, Huecorio. In an old house we installed our first workshop without imagining what would happen with time.

Q: What made you choose this topic?

A: One day walking along the shore of the lake, we discovered an immense blooming weed; it was really magical. We took a couple of plants from the shore and brought them home for decoration.

We really did not know anything about the water lily “Eicchornia Crassipes.”

We had a 2-liter glass cube and we filled it with water and deposited the plants.We went on a trip for a couple of weeks, and when we returned the bucket was empty and the plants were still alive. They were stuck to the glass: where did the water go? We thought that the cube had a (crack), and decided to fill it again, but the cube had no leak. I was suspicious, so I decided to mark the cube with millimeters and observe.

As days went by, we witnessed the natural effect of a plant that devoured water. Then we went to the books, to the internet articles and every time we delved into the subject, we were more astonished.

This plant is not local to Mexican lakes. It is originally from Brazil. We initiated biological research on its potential geographical proliferation.

Its enormous density offered material possibilities for art… and bingo! We discovered that the water lily is excellent for making exotic paper.

Q: How did you first learn about this environmental hazard?

A: We found that the lily is stimulated by the pollutants that we pour into the water.

When we carried out tests on the behavior of the plant in clean water, the results were surprising. The lily thinned and drastically reduced in size, so we discovered that the environmental problem is due to the proliferation of the water lily, which grows best in contaminated water itself.

Here, the project took on its social form. We urgently question our relationship with the environment and the disastrous repercussions due to the carelessness of a society.

Q: How did you decide to start this project?

A: Every time we investigated the repercussion of the phenomenon of eutrophication (water runoff making the lake nutrient rich) and the desiccation (drying) of the lake, we found ourselves with more problems. For example, there’s the deforestation, the exploitation of the springs, the extinction of migratory bird species by illegal hunting and the disappearance of (native) fish from a private lake.

We have witnessed in the last 18 years the impoverishment of our ecosystem and its natural resources, an issue that generates poverty and, as a consequence, migration of people to other Mexican states — but mainly to the U.S.

Once we managed to manufacture the first sheets of paper based on water lily, we decided to start a production workshop to be able to sell the products and economically support our campaign for environmental awareness.

Q: Do you have a background working with the environment?

A: We do not. We have tried to make contact with federal funding but we have not achieved anything. The money earned for lake rescue programs is spent in a big bureaucracy.

We have the help of some generous friends, and thanks to some art scholarships that we have won in competitions for cultural projects, we have built the project.

Q: What do you expect this project to achieve?

A: We want to stop the continuing environmental disaster of the territory.

With a cultural awareness shift in the community, hopefully the authorities will install efficient treatment plants. In our workshop, we hope to achieve a paper-making tradition with the domestication of this wild aquatic plant and create a green production chain that benefits women, single mothers and unemployed young people.

Q: If someone wanted to help in this cause, what can they do?

A: We need donations to finance cultural programs around the lake, so we have a system of “bartering” or exchange of products.

People who buy packages of DeLirio, our paper products, can support the operational and survival costs of our workshop. Our initiative is completely independent.

For any artists who want to come to create and share an original production, we have equipped our workshops for papermaking, engraving, screen printing, typography and binding.

With technical assistance from our work team, we have a cafeteria, paper shop and tours around the lake. Artists can visit other artisans and will have lodging, food and wifi.

Q: What has the reaction been from your community?

A: At first the (reaction) was very hostile. Being “foreigners” in indigenous territory (with historical reason for the contempt of these peoples), it took us a few years to adapt to the village’s customs.

Tania, and our children are in the best situation to promote new ways of creation. We can organize and fight for the improvement of our environment, culture and livelihood.

Since 2016, Silva and Dominguez have been inviting artists to their studio, Taller De-Lirio, in order to participate in the poster project “SOS for Lake Patzcuaro.” Thirty-two local artists helped create a total of 64 environmental-themed posters with social undertones.

The exhibition opened Oct.1 and will run until on Jan. 11. The SCC art gallery hours are from 9 a.m.-5 p.m., Monday through Friday.