HOW WE CHOOSE OUR CURRICULUM

For students at SCC, required classes are a familiar sight. English 101 and Multicultural Studies are just a couple of examples of the core requirements that grace the top corner of planning guides — but what about sustainability?

What Is Sustainability?

1987’s Brundtland Report, which served to unite all nations for a global understanding of sustainability, defines sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Although commonly associated with environmental issues, sustainability isn’t limited to that subject — it also covers broad subjects like economy and society.

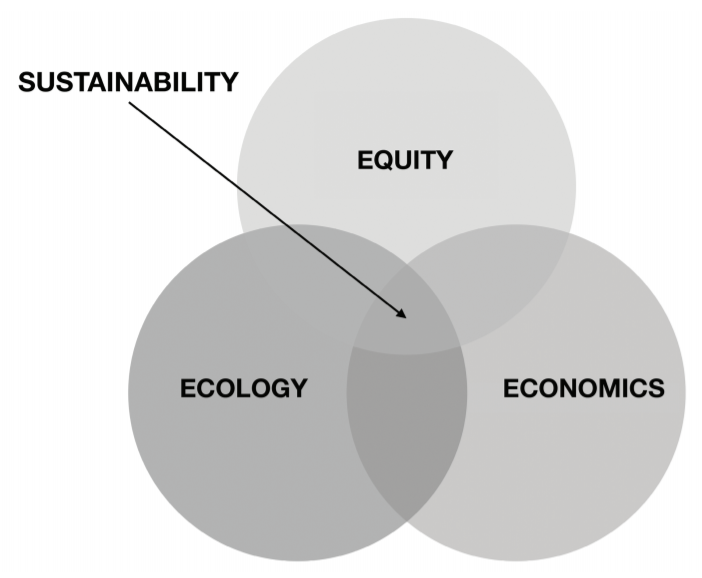

That idea can be summed up with what SCC refers to as the Three E’s: economics, meaning something is economically feasible; equity, meaning social equity is considered; and ecology, meaning it is environmentally sound.

Themes of sustainability occupy the third goal of SCC’s Strategic Plan (an outline of the college’s mission and how it will be successfully carried out).

The goal ensures that “a climate of intentional inclusion permeates our decisions and practices, which demonstrate principles of ecological integrity, social equity and economic viability.”

The plan also states this will be done by engaging in conversation on the subject, allowing an ecological mindset to steer practices and developing resources.

Considering SCC’s interest in sustainability, why might such a broad and important area of study not be a general education requirement at our college?

Emma Agosta, Chip Dodd and Tim Payne are SCC professors who focus on sustainability. All three have been involved in related programs at the college SCC for over 10 years, and have served on the Ecological Integrity Steering Committee (EISC).

Agosta, who teaches geology at SCC, serves as the faculty program coordinator for earth sciences. Dodd teaches both geography and international studies, and Payne teaches economics and international studies along with having done sustainable development work in Southeast Asia and Central America.

Payne and Dodd teach a class on international political economy together, which contains environmental themes that transcend geographical borders such as climate, oceans and endangered species.

Payne explains that sustainability occurs where ecological, equity and economic goals intersect. Additionally, he describes sustainability as a multi-disciplinary way of looking at managing resources and meeting human needs now and into the future.

Why Isn’t It Required?

Agosta says that the process of establishing general education requirements is a complex one that begins with faculty and is ultimately decided by SCC’s Curriculum Committee.

She says that the decision behind SCC’s current core requirements most likely resulted from decades of faculty trying to determine a common ground for what can be deemed essential for student learning.

When it comes to the prospect of sustainability becoming a core requirement, Agosta explains that the conversation hasn’t necessarily expanded beyond the college’s tight-knit sustainability faculty.

Agosta says that although the idea is something that the faculty are interested in exploring and discussing, they don’t see it happening in the near future without first going through the rigorous decision-making process.

Dodd adds that even though SCC is ahead of the curve in terms of both the country and the northwest regarding its required multicultural curriculum, the same doesn’t yet apply to sustainability studies.

“We’re seeing it more and more in the established curriculum of four-year schools,” Dodd says of sustainability and the Three E’s.

Dodd and Payne both agree that although it would be nice to see sustainability as a general education requirement, it would first need to begin with a grassroots or “ground-up” movement that allows students and faculty from all areas of study to be able to relate and understand the subject.

“That’s how it’s going to create the change the world needs,” Payne adds.

Earlier this year, the EISC at SCC conducted a survey via email to ask students and faculty about their opinions on environmental sustainability in education.

- Out of 498 students, 93 percent answered “neutral,” “maybe” or “yes” when asked if they felt that a course that focuses on environmental sustainability is “essential to a well-rounded general education curriculum.”

- Out of 497 students, 79 percent answered “neutral,” “maybe” or “yes” when asked if they thought that SCC students “should be required to take at least one course that focuses on environmental sustainability.”

- Out of 524 students, 80 percent answered “maybe” or “yes” when asked if they would like to take courses that “focus almost entirely on the environment or sustainability.”

- Out of 523 students, 83 percent answered “maybe” or “yes” when asked if they would like to take courses that “included content (e.g., module, chapter, assignment) focusing on the environment or sustainability.”

Nova Clark may have participated in this survey.

Sustainability In Other Courses

There could be alternate ways to bring sustainability into SCC’s focus.

Agosta explains that instead of having sustainability as an extra core requirement on the list needed to graduate, a shorter-term option could be infusing existing requirements and their course material with themes of sustainability through individual units or modules.

“I think the conversation has to be broader in terms of how we want to do it,” Agosta says. For example, music classes could host outdoor showcases, which would simultaneously get students more in touch with nature and allow faculty to turn off electricity upon leaving the music building for the day earlier than they might have normally.

“It needs to be infused throughout more and more classes, academic disciplines, faculty and the broader curriculum.” Payne says, noting how SCC’s survey results reflected a faculty interest in teaching courses related to sustainability or bringing it into their existing lessons.

“That shows that there might be some untapped resources out there, and that gives us a chance to expand the idea amongst our faculty,” he says. “And that’s where the momentum for making it a requirement might come from.”

This way, provided the resources, faculty could incorporate as little as one sustainability-related lesson into their existing course without a lot of change. An English class, for instance, could require a reading or an essay on the topic.

Living Laboratories

One way sustainability can be incorporated into other classes is to utilize the campus’ surrounding foliage as what Payne calls a “living laboratory.”

He has been employing hands-on methods of teaching alongside Dodd and Agosta for a number of years noting that very few campuses have a thriving forest like SCC does.

But the idea isn’t limited to the greenery: For example, the SCC Economics Research Group (which Payne led), established water bottle refilling stations around the college.

Along with using the campus as an operational “laboratory,” the club’s accomplishment incorporated the Three E’s: economics by eliminating the need to buy bottled water, equity by providing drinking water to all students across campus regardless of ability to pay and ecology by reducing the use of plastic.

“We could be doing a whole lot of projects like that around campus,” Payne says.

To learn more about the increasing emphasis on sustainability in colleges, visit The Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education at aashe.org